BOW VALLEY – It’s a delicate dance between man and mountain with every step, every glide, every swing of an ice axe on a towering frozen face.

You study your dance partner and try to predict their movements, but mountains and the forces of nature are, by design, sometimes unpredictable and often unforgiving.

For ice climbers, the stakes around avalanche fatalities have historically been high and, until recently, not as well-understood as many who’ve been climbing for decades feel they should be.

Canmore’s Sarah Hueniken, a professional climber, alpine guide and ice climbing ambassador for Avalanche Canada, knows the stakes better than most. On March 11, 2019, an avalanche tragically killed one of her close friends, Sonja Findlater, at Massey’s Waterfall, a popular ice climbing route in Yoho National Park.

It’s Hueniken’s ‘why’ for creating an Ice Climbing Atlas, with the help of pioneer and leader in avalanche safety Grant Statham, who works for Parks Canada’s Banff, Yoho and Kootenay field unit as a visitor safety specialist.

“The impetus for it, for sure, was after the Massey’s accident. I’ve spent years just asking myself what we all could have done more to understand. … We knew the potential, that was clear and obvious, but just using the tools that we had with the avalanche forecast and our familiarity, talking to Parks and other guides and still feeling like this was a good place to go,” said Hueniken, who was one of the guides on the multi-day camp.

“Was there anything more that could have helped us with our decision-making?”

When Hueniken was later approached by Avalanche Canada to be the non-profit’s first ice climbing ambassador, she saw it as an opportunity to identify gaps in information and knowledge-sharing in the ice climbing community.

Long before she was backed by the non-profit, the climber of 25 years often wondered why more historical avalanche information on ice climbs in the Bow Valley didn’t exist, apart from by word-of-mouth and more recently, social media, which she noted is useful but also full of “armchair experts.”

“They have big avalanche atlas maps for highways where it shows the paths and frequencies. They really understand the frequency of these paths that affect highways because they have to, they’re industry standard and people drive them all the time,” she said.

“Obviously the need isn’t as great for recreational and guided ice climbs to really understand the terrain in the same way, but I thought, ‘why can’t we? Why can’t we try to know more?’

“To know this climb avalanches this many times a year normally or what causes it to avalanche or what are the factors,” she said.

Hueniken’s initial focus with Avalanche Canada was to promote avalanche awareness in the ice climbing community through its Mountain Information Network – a tool for users to share real-time, location-specific information about avalanches, snowpack, weather and incidents.

“They had done snowmobiling and skiing and a bit of hiking, but never ice climbing. So, I agreed to be the ambassador and through that, I kind of could do what I wanted to do if I brought a good idea to them,” she said.

The non-profit picked up her next good idea, the Ice Climbing Atlas – an ongoing project that started about three years ago compiling avalanche frequency and historic avalanche information via data crowdsourced from online surveys.

Respondents are asked how often they climbed a route, when, in what conditions, whether they witnessed an avalanche, and how often avalanche debris could be seen in gullies. It was important to understand whether avalanches occur more than once a year, annually, or every 10 years or more.

“The results of the survey showed that most respondents experienced avalanches more than once per year. This indicates that avalanches are a common occurrence and should be taken seriously by climbers,” states a paper on the atlas co-authored by Statham and Hueniken, which was presented at the International Snow Science Workshop in Bend, Oregon Oct. 8-13.

Where Hueniken carries out surveying for the atlas, Statham and partners with Alberta Parks’ Kananaskis Mountain Rescue (KMS), assist with avalanche path mapping and terrain data.

The Outlook contacted Alberta Parks’ to speak to a rescue specialist about the use of the Ice Climbing Atlas in aiding with public safety in Kananaskies. Instead, they offered a statement saying the agency had been asked to provide slide paths and rating scale assessments for Kidd Falls, King Creek and Ranger Creek and ratings for Tasting Fear.

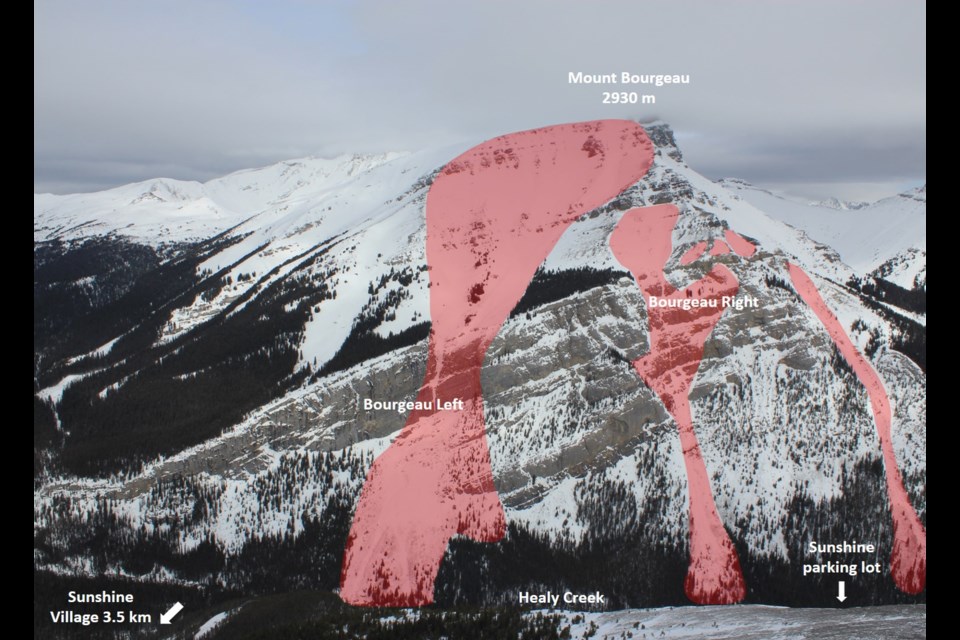

The result of the partnership is detailed avalanche path information for 20 popular waterfall ice climbs and counting in the Bow Valley and surrounding area, each rated by the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES), which was developed by Statham in the early 2000s and is used worldwide.

So far, the atlas contains popular ice climbs like Cascade Waterfall, Guinness Gully, Louise Falls, Polar Circus, Urs Hole and Ranger Creek in Kananaskis Country, where one person was killed in a size 2 avalanche that involved two people Nov. 11.

Statham and Hueniken’s paper found climbers were second to skiers in avalanche fatalities in Banff, Yoho and Kootenay national parks over the last 25 years. Of the deaths recorded, there were 13 skiers, 10 climbers, five snowshoers and two tobogganers.

“Considering that the number of skiers in these parks far exceeds the number of climbers, climbers likely have a substantially higher risk of dying from avalanches than skiers,” the paper states. “Furthermore, the nature of the climbing accidents is different, because 70 per cent of those climbers killed by avalanches were hit by natural avalanches that started overhead.”

It also noted avalanche forecasts are “often biased towards human triggering for skiers, rather than forecasting for natural avalanche release,” which it adds is “highly uncertain and has more in common with highway avalanche forecasting than it does with backcountry recreation.”

The report notes professional avalanche atlases are standard for areas such as ski resorts and transportation corridors, providing geographic data and visuals collected over decades.

“This information has often been collected for decades, and the data facilitates accurate estimates of avalanche frequency and runout distance. This is not the case for ice climbs where until now, nobody has systematically collected avalanche information,” the report states.

Assessing factors such as slope angles, shape of terrain, frequency of avalanche and availability of options for climbing routes applies an ATES rating to each ice climb in the atlas.

Another consideration to assessing risk is how long an ice climber might spend in one spot versus someone ski touring, for example.

“Ski tourers would move through an avalanche path and then they step out of it and then go somewhere else. They’re not under it all day long. Whereas ice climbers will often spend most of their day in one avalanche path because they’re in a big gully,” said Statham. “We’re trying to talk about how frequent that avalanche path runs.”

A high-frequency path would be one that is known to run multiple times per year. A very low-frequency path would be a path that runs once every 30 years or more.

“It’s a combination of frequency of the avalanche and then actually the time that the people are exposed for. Your risk is going to be higher the longer you’re there,” said Statham.

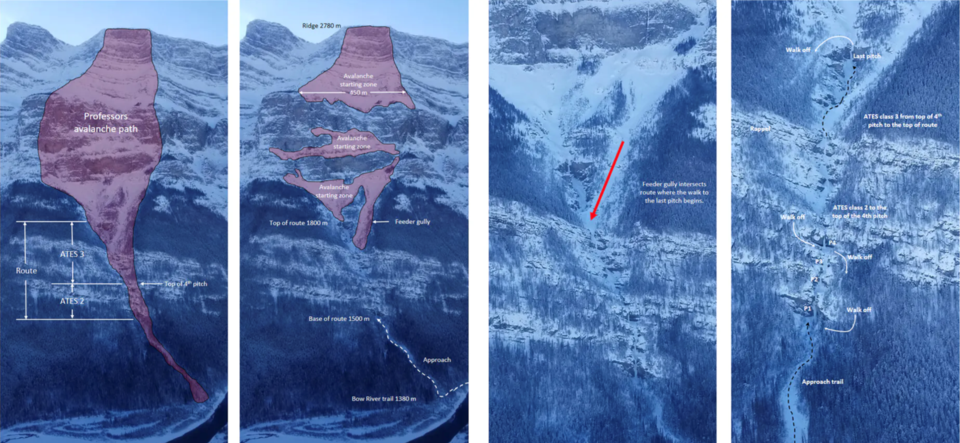

Professor Falls, a popular four-pitch ice climb on Mount Rundle in Banff National Park, which is approached from the Banff townsite, has two ATES ratings – ATES 2 and ATES 3 – representing challenging conditions through the first through fourth pitches and complex conditions to the top of the route.

“If somebody wants to climb Professor all the way to the top, they’re going to be entering a place where avalanches come through there every year. That’s different than the lower part of Professor’s, where, it’s not every year there’s an avalanche on the lower part – it’s less frequent than that. So, we expect it to be a less risky place, so to speak.”

Directly above the falls are three different avalanche start zones up to 450 metres wide that run down the same avalanche path, as noted in the atlas.

Including measurements of avalanche start paths and the length it may run was intentional to give climbers a sense of the magnitude of what’s overhead, said Statham.

Of 109 people surveyed about Professor Falls, 84 per cent said they saw avalanche debris on the route and 20 per cent witnessed an avalanche in the area.

Those surveyed found 59 per cent believed contributing factors for avalanches were from winds, 53 per cent from new snow, 44 per cent from warming, 18 per cent from a known weak layer and 12 per cent from a cornice or human/animal trigger.

One of the incident reports for Professor Falls notes a person was “critically buried” by an avalanche between the second-last pitch and had to be dug out using a helmet.

Another person reported finishing the final pitch of the climb and hiding against the side of the gully as an avalanche slid past, “piling up metres of snow right next to us.”

Hueniken said as an ice climber, it’s important to review topography maps such as FATMAP to understand the geography of a climb and know what you’re walking into.

But, she added, there’s nothing better than seeing an actual image of the climb, which until now most did not have access to. Statham, in his position with Parks Canada, along with rescue specialists with Kananaskis Mountain Rescue, are often in the field and in a position to take such photos from a helicopter or drone.

“With so many ice climbs you’re approaching in the dark. As you’re approaching you don’t see that terrain,” said Hueniken. “You don’t see all day long actually what’s happening above you unless you can get one of these kinds of overhead shots.”

Statham said by presenting accurate information with good visuals, the hope is more people will have a more accurate sense of terrain hazards and check the atlas to aid in planning and navigating routes safely.

“Ice climbers have not historically been great at avalanche awareness. For many years – not now – but for many years, ice climbers and avalanches seemed to be kept a little bit separate despite the fact that climbers – and I would count myself in this category – spend a lot of time in huge avalanche terrain,” said Statham.

The ice climbing atlas, alongside avalanche forecasts, condition reports and weather station data on Avalanche Canada’s website, offers a comprehensive stream of avalanche information for ice climbers.

Avalanche Canada program director James Floyer said it is the responsibility of the person climbing to use the atlas’s information and combine it with their own local knowledge and observations of what’s happening with the weather and recent incident reports.

The non-profit is working with Statham and Hueniken to improve mapping on its website and make the atlas information easier to view as a layer from the homepage map.

“We’re trying to find ways that we can provide valuable information, and we’re trying our best to reach out to the ice climbing community to see what their needs are, but we’re also receptive to suggestions and input from the ice climbing community to help us improve these kinds of resources,” said Floyer.

Hueniken is pleased to offer the atlas to ice climbers – it is 100 per cent a volunteer effort. But the last thing she wants is for climbers to feel safe with it. In the mountains, there is a lot you can do to make an experience safer, but you simply can’t control every outcome.

“The Atlas is created because of the Massey’s accident. … I wouldn’t be here doing this right now if that hadn’t happened,” Hueniken said.

To wonder if it could have prevented an avalanche fatality or believe it might in the future is futile measured up against the forces of nature.

“That’s bullshit. This atlas is really just another tool. People are still going to die in avalanches. They’re still gonna go ice climbing – it’s gonna happen," she said.

“We can learn lots and there’s great learnings to be had, but it’s never gonna be safe.”

The Local Journalism Initiative is funded by the Government of Canada. The position covers Îyârhe (Stoney) Nakoda First Nation and Kananaskis Country.

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)